It’s that time of the year where I’ll be making my way to Redmond (Washington, USA) to attend the MVP Global Summit 2016.

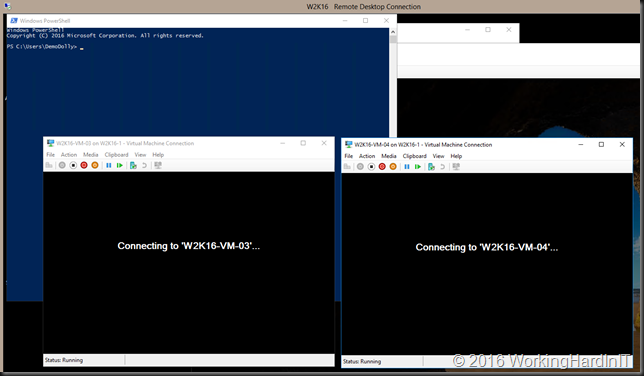

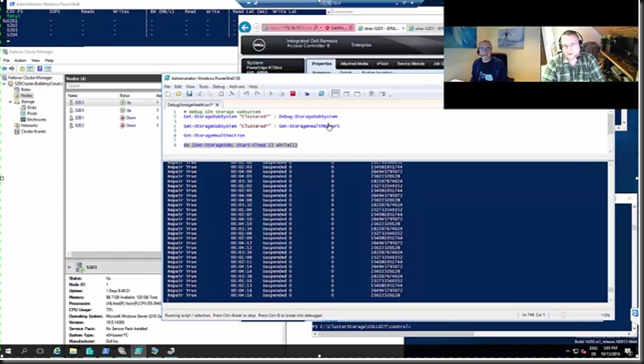

It’s going to be and interesting one as after 2 years of Technical previews Windows Server 2016 went RTM last September and is generally available. Our hardware partners are selected for best value and that means early and good support for new releases of Windows. Dell, Emulex, Intel and Mellanox delivered and that means we can already share our first real life experiences around the finished product with Microsoft.

We’ll also be talking shop about future directions and provide feedback on what we want to see happen and need. Next to Windows (which is so much more than “just” an operating system nowadays) we have a stake in SQL Server 2016 and Azure. Azure in all it’s offerings, SAAS, PAAS, IAAS – both public and hybrid use cases.

To do so we need to get there first so we’ll hop on a Boeing (hey I’m flying to Washington, kind has to be a Boeing right?) for long haul a flight to Redmond and go talk shop all week long from early dawn at breakfast to night caps in downtown Bellevue with friends and colleagues.

Next to pure technology we also talk about business challenges and opportunities. The best positioned organizations are the ones where the technical people have taken and been given the opportunity to lead. I know it’s scary for some managers that feel threatened by this but when the techies lead the IT side of the business the rest can can focus on the business and avoid the costly mistakes that I see so many make today. Most organizations have failed at getting business people up to speed on IT. I’ve seen a lot of successful organizations let technical people show how the business how to thrive in a mobile and cloud first world. It just makes sense to let your experienced and talented technical people take the lead. Don’t think for one second that they’re just janitors mopping the floor in an outdated server room when not busy handling the “other” facilities. Do that and you will fail painfully. Put away your politics, fears, long term gigantic projects and learn to let fast, inexpensive, simple, small technology solution rule in a federated world to maximize time to market, results and flexibility. If you don’t let go of centralized, long term, overly complex technology projects and old school enterprise solutions – where everything is held by back by everything else – you’ll fail, lose vast amounts of money and time. Don’t!